How Renaissance Technologies Solved the Market: Part 3 — Incentives

Renaissance Technologies is the most successful hedge fund in history, netting investors an average of 39% a year after fees over the last 3 decades. Renaissance stands out among its peers as by far the best performing fund.

One reason is that the incentives Renaissance decided to focus on are different than that of other funds.

This is part 3 of my thoughts on Renaissance Technologies after reading The Man Who Solved the Market. Part 1 discussing the Renaissance data pipeline can be found here. Part 2 discussing the Renaissance unusual practice of hiring from academia can be found here.

Incentives

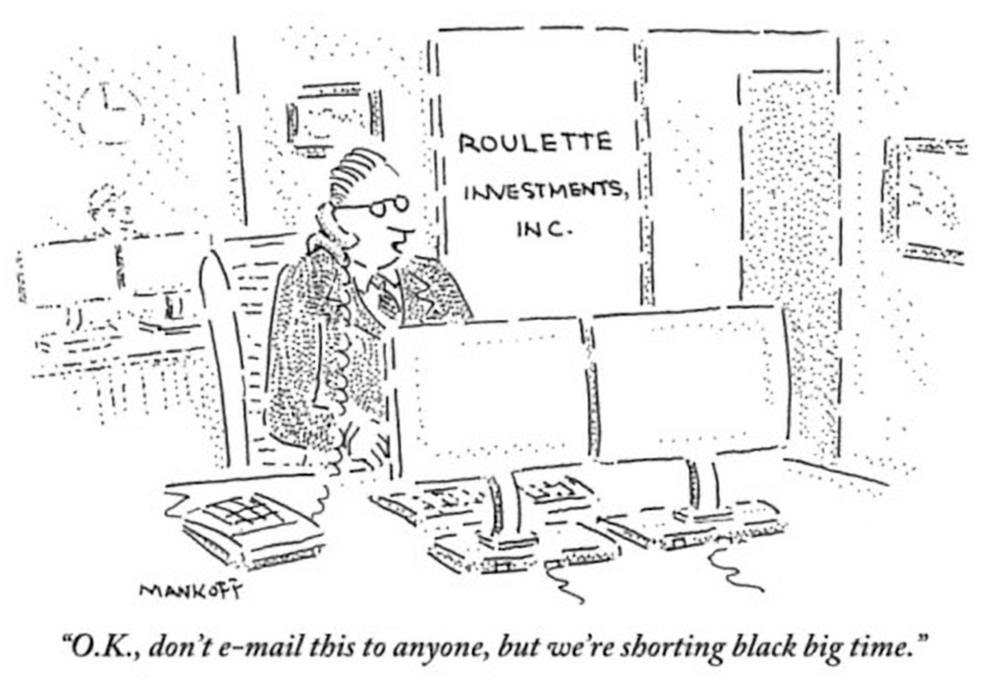

In Zero to One Peter Thiel considers the following proposition: companies exist to make money, not to lose it. This should be obvious but consider the frame of reference. Do hedge funds exist to make money for investors or the owners? Ideally both, but what if a manager had to choose?

Hedge funds generally make fees in two ways: a fixed management fee based on assets under management (AUM) and a performance fee based on a percentage of returns above a certain benchmark. Generally these fees have been 2% and 20%, respectively.

For instance, if a fund is managing $100 million and makes 20% return while their benchmark made 10%, the total fee would be $4 million:

Management fee: 0.02 * 100mm = 2mm

Incentive fee: 0.2 * (0.2 — 0.1) * 100mm = 2mm

If the fund didn’t beat the benchmark or lost money, they would only make the management fee of $2 million.

As a manager, what would you optimize for? I’m no expert, but to me it seems easier and cheaper for funds to raise $100 million than it is to beat the market by 10%. In fact, it may not even be possible to beat the market. Very few funds have a consistent record and the efficient market hypothesis suggests that prices reflect all available information, so there is no practical way to find mis-priced assets. So funds generally optimize for managing larger AUM over investing in trying to beat the market. Or they open multiple uncorrelated funds to diversify their revenue stream.

Renaissance is different. Jim Simons always optimized for performance. Renaissance originally found success in trading futures, currencies and commodities. At the time, these markets followed patterns that were easily discernible to a computer. The strategies employed were trending (price will continue to move in same direction) and mean reversion (price will return to original value). But this market was not large enough to grow the fund and maintain performance. In order to grow, Renaissance needed to find a profitable strategy for stocks.

Simons was experimenting in the stock market since the late 1980s but the strategy that had worked well on futures was not working on equities:

Simons acted too quickly, it turned out. It soon became clear that the new stock-trading system couldn’t handle much money, undermining Simons’s original purpose in pushing into equities. Renaissance placed a puny $35 million in stocks; when more money was traded, the gains dissipated, much like Frey’s system a couple years earlier. Even worse, Brown and Mercer couldn’t figure out why their system was running into so many problems

Simons persisted however and refused to put in much money until he had solved the problem. Finally, in 1995 one of the early engineering hires, David Magerman, discovered the problem:

Early one evening, his eyes blurry from staring at his computer screen for hours on end, Magerman spotted something odd: A line of simulation code used for Brown and Mercer’s trading system showed the Standard & Poor’s 500 at an unusually low level. This test code appeared to use a figure from back in 1991 that was roughly half the current number. Mercer had written it as a static figure, rather than as a variable that updated with each move in the market.

Once that bug was fixed, the model began performing better.

When Magerman fixed the bug and updated the number, a second problem — an algebraic error — appeared elsewhere in the code. Magerman spent most of the night on it but he thought he solved that one, too. Now the simulator’s algorithms could finally recommend an ideal portfolio for the Nova system to execute, including how much borrowed money should be employed to expand its stock holdings. The resulting portfolio seemed to generate big profits, at least according to Magerman’s calculations.

Only then did Renaissance commit significant capital into the equity markets. The focus on performance originally held the company back in terms of its size, but once the market was cracked, Simons had the confidence to grow the fund while all but guaranteeing strong performance.

Why Hasn’t It Been Replicated?

As mentioned above, its easier to make money by raising AUM than it is actually beating the market. Even funds that purport a quantitative investment strategy similar to that of Renaissance don’t do well:

For all the advantages quant firms have, the investment returns of most of these trading firms haven’t been that much better than those of traditional firms doing old-fashioned research, with Renaissance and a few others the obvious exceptions. In the five years leading up to spring of 2019, quant-focused hedge funds gained about 4.2 percent a year on average, compared with a gain of 3.3 percent for the average hedge fund in the same period. (These figures don’t include results from secretive funds that don’t share their results, like Medallion.)

Another strategy is for funds to offer investors exposure to a certain market in exchange for a fee. For instance, you can buy into funds that invest in shipping containers, which would be difficult to invest in without expertise. The funds performance is clearly tied to the underlying market and is mostly passive. But the fund still gets its relatively large management and performance fees. And with each hedge fund managing multiple funds with different strategies, they can play games with purported returns (e.g. close poor performing funds and benefit from survivorship bias in reporting returns).

Other quant funds such as Long Term Capital Management (LTCM) hired brilliant people and enjoyed early success but eventually their incentives were perverted as they took on more risk and leverage and expanded to unfamiliar markets:

Mesmerized by LTCM’s all-star team of brainiacs, investors poured money into the fund. After launching in 1994, LTCM gained an average of nearly 50 percent in its first three years, managing close to $7 billion in the summer of 1997, making Simons’s Medallion fund look like a pip-squeak. After rivals expanded their own arbitrage trades, Meriwether’s team shifted to newer strategies, even those the team had little experience with, such as merger-stock trading and Danish mortgages.

Even the smartest people can fall victim to incentives.

After an annual golf outing in the summer of 1997, LTCM’s partners announced that investors would have to withdraw about half their cash as a result of what executives saw as diminishing opportunities in the market. Clients lost their minds, pleading with Meriwether and his colleagues — please, keep our money!

But eventually the fickle, over-extended strategy of LTCM blew up in their faces and Meriwether no longer had the problem of too much capital. Rival fund D.E. Shaw suffered a similar fate:

Then came the market turmoil of the fall of 1998. Within months, D. E. Shaw had suffered over $200 million in losses in its bond portfolio, forcing it to fire 25 percent of its employees and retrench its operations. D. E. Shaw would recover and reemerge as a trading power, but its troubles, along with LTCM’s huge losses, provided lasting lessons for Simons and Renaissance

Bridgewater’s Ray Dalio similarly seems to be selling a management philosophy rather than actual returns. He’d rather spend his money on a public relations team to write puff pieces on his firm. Most stories have a single throw away line somewhere in the middle that says Bridgewater returns have lagged passive index funds. Or they just focus on returns from Pure Alpha. If those returns aren’t stellar, check out Pure Alpha II, or the All Weather Fund. Something for everyone.

But who cares about that when Bridgewater is developing an artificial brain to mimic its founder’s mediocre decision making. Why would Dalio want to write an algorithm meant to mimic his brain rather than an algorithm that can make investment decisions directly? Because the former is much harder to assess and identify as a fraud. It’s more profitable to sell AI snake oil and pay off journalists not to ask obvious questions.

Meanwhile Renaissance managed $110 billion and had only 290 employees as of 2015 operating out of a modest office in East Setauket, Long Island. Obviously Renaissance has chosen a different set of incentives to optimize.

The other important thing to note is that the best performing fund of Renaissance, the Medallion Fund, is available only to employees. The returns are so strong that they forgo growing the fund so that their strategy remains effective.

In the next part, I will discuss the strategy Renaissance uses.